by Andrea R. Olinger

What do you get when you take 235 sophomore computer engineers, remove two of their exams from the curriculum, and replace them with a pair of collaborative projects? The usual gripes from students about unfair labor distribution and, for some students, limited learning? Or raves about enriching teamwork experience and deeper understanding?

For the past two years, researchers at Illinois have explored this question, seeking to increase students’ intrinsic motivation in required engineering courses without creating more work for instructors. (See the project website here.) Geoffrey Herman, the project lead, explained that education reform efforts typically focus on students’ “cognitive outcomes”: “Did they learn X amount more? Do they not have these misconceptions? Did they learn X skill?” But, he declared, “motivation plays a huge role in cognition. If you simply motivate students more, they’re going to learn more.”

Geoffrey’s research team has spent considerable time reworking engineering courses around self-determination theory, which asserts that motivation arises from a person’s needs for purpose, autonomy, relatedness, and competence. For Computer Engineering I (ECE 290), in which students learn how to build computer hardware, groups of four or five students work on circuit design problems that they invent themselves.

In addition to providing students with teamwork experience they don’t get in earlier engineering courses, the instructors hope to offer “more choice and more autonomy in a required course in which typically students have no choice,” explained Michael Loui, who is co-teaching the course with John Stratton. “Why,” Michael asked, “should we be delaying the good stuff” until students’ junior and senior years?

Geoffrey, Michael, John, and the research team have a number of tricks for making the projects successful:

- Instructor-assigned groups of mixed ability levels. Students are assigned to groups partly based on their ability levels, ensuring there is a range in each group. (They use the CATME team-maker tool to do so.) Because of this assignment, Michael estimated that “the quality of the projects should be roughly similar, so any variance in grades will be due to the individual component, which is as it should be.”

- Individual accountability. Students’ grades comprise not just scores on the team portfolio and final project report but also peer ratings and an individual score—involving individual contributions to team deliverables and self-evaluations and reflections.

- Ongoing feedback. Teams decide on their tasks and timeline but have mandatory weekly consultation sessions with an instructor or TA, who provides feedback along the way. Although students attend two lectures and one discussion section in addition to this consultation, the sessions have another purpose: students who wish to earn points can present their answers to one of the week’s homework problems—and get instant feedback from the instructor or TA. The consultation sessions, as a result, are more integral to students’ success in the course, not simply another thing to do.

- Training in project management and collaboration. Students receive guidance in project management and teamwork. As the “Learning Team Guidelines” on the course website explain, groups must select a project manager, develop a team charter and revise it after the first project, and maintain a task schedule. (They are also encouraged to choose a team name that reflects their common interests or expresses a collective personality.) The guidelines also address effective meetings and collaborative writing, drawing partly on Joanna Wolfe’s book Team Writing in suggesting a “layered” approach over a “divide and conquer” one.

- Learning linked to individuals’ goals. Students are asked to reflect on their personal goals for the course and connect them to the projects. A written reflection assigned at the start of the course, for instance, asks students to describe the professional skills they hope to acquire by working in a team, the computer engineering topics outside of ECE 290 that they hope to learn, how these skills and topics relate to their career goals, and what experiences and skills they can contribute to their team. Two further reflections, one after each project, ask students to review their initial reflection (and self- and peer-evaluations) and think about what new skills they developed and topics they learned. Also, when groups divvy up tasks, they are encouraged to do so based on who is most motivated to learn a particular skill, not who has the greatest knowledge of it. (The latter person can be a mentor.)

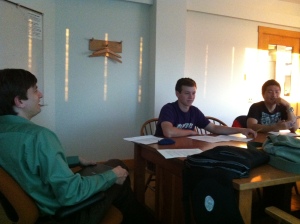

At their second consultation with instructor John Stratton, team “Five-Sided Die” was both nervous and excited for what lay ahead. Most hadn’t worked in teams quite like this before. Junior Tae Yeon Kwon explained that he felt more motivated by this kind of structure because “you’re not working alone. Other people are going to count on you.” Trevor Freberg, also a junior and the group’s project manager, declared that with projects, “we kind of control our own destiny.” As opposed to when you cram for an exam, “we know what we’re going to get, we know what we have to do.”

If history is any indication, team “Five-Sided Die” will emerge successful—and not just extrinsically so. In previous semesters of this reengineered curriculum, Geoffrey reported that students felt excited to be part of a “supportive network of people” who cared about their learning and from whom they could draw inspiration and energy. And many “went from wanting to get the easy A to taking on some pretty ambitious projects and trying to do some things to really challenge themselves.”

In two months, what will team “Five-Sided Die” have created and become? We’ll check back with them and the instructors at the end of the semester.